Breast cancer

| Breast Cancer | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

Mammograms showing a normal breast (left) and a breast cancer (right). |

|

| ICD-10 | C50. |

| ICD-9 | 174-175,V10.3 |

| OMIM | 114480 |

| DiseasesDB | 1598 |

| MedlinePlus | 000913 |

| eMedicine | med/2808 med/3287 radio/115 plastic/521 |

| MeSH | D001943 |

Breast cancer (malignant breast neoplasm) is cancer originating from breast tissue, most commonly from the inner lining of milk ducts or the lobules that supply the ducts with milk. Cancers originating from ducts are known as ductal carcinomas; those originating from lobules are known as lobular carcinomas.

Prognosis and survival rate varies greatly depending on cancer type and staging.[1] Computerized models are available to predict survival.[2] With best treatment and dependent on staging, 10-year disease-free survival varies from 98% to 10%. Treatment includes surgery, drugs (hormonal therapy and chemotherapy), and radiation.

Worldwide, breast cancer comprises 10.4% of all cancer incidence among women, making it the most common type of non-skin cancer in women and the fifth most common cause of cancer death.[3] In 2004, breast cancer caused 519,000 deaths worldwide (7% of cancer deaths; almost 1% of all deaths).[4] Breast cancer is about 100 times more common in women than in men, although males tend to have poorer outcomes due to delays in diagnosis.[5][6][7][8]

Some breast cancers are sensitive to hormones such as estrogen and/or progesterone which makes it possible to treat them by blocking the effects of these hormones in the target tissues. These have better prognosis and require less aggressive treatment than hormone negative cancers.

Breast cancers without hormone receptors, or which have spread to the lymph nodes in the armpits, or which express certain genetic characteristics, are higher-risk, and are treated more aggressively. One standard regimen, popular in the U.S., is cyclophosphamide plus doxorubicin (Adriamycin), known as CA; these drugs damage DNA in the cancer, but also in fast-growing normal cells where they cause serious side effects. Sometimes a taxane drug, such as docetaxel, is added, and the regime is then known as CAT; taxane attacks the microtubules in cancer cells. An equivalent treatment, popular in Europe, is cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and fluorouracil (CMF).[9] Monoclonal antibodies, such as trastuzumab (Herceptin), are used for cancer cells that have HER2/neu overexpressed. Radiation is usually added to the surgical bed to control cancer cells that were missed by the surgery, which usually extends survival, although radiation exposure to the heart may cause damage and heart failure in the following years.[10]

Contents |

Classification

Breast cancers can be classified by different schemata. Every aspect influences treatment response and prognosis. Description of a breast cancer would optimally include multiple classification aspects, as well as other findings, such as signs found on physical exam. Classification aspects include stage (TNM), pathology, grade, receptor status, and the presence or absence of genes as determined by DNA testing:

- Stage. The TNM classification for breast cancer is based on the size of the tumor (T), whether or not the tumor has spread to the lymph nodes (N) in the armpits, and whether the tumor has metastasized (M) (i.e. spread to a more distant part of the body). Larger size, nodal spread, and metastasis have a larger stage number and a worse prognosis.

The main stages are:

Stage 0 is a pre-malignant disease or marker (sometimes called DCIS, Ductal Carcinoma in situ or LCIS, lobular carcinoma in situ) .

Stages 1–3 are defined as 'early' cancer with a good prognosis.

Stage 4 is defined as 'advanced' and/or 'metastatic' cancer with a bad prognosis. - Histopathology. Breast cancer is usually, but not always, primarily classified by its histological appearance. Most breast cancers are' derived from the epithelium lining the ducts or lobules, and are classified as mammary ductal carcinoma or mammary lobular carcinoma. Carcinoma in situ is growth of low grade cancerous or precancerous cells within an isolated pocket without invasion of the surrounding tissue. In contrast, invasive carcinoma invades the surrounding tissue.[11]

- Grade (Bloom-Richardson grade). When cells become differentiated, they take different shapes and forms to function as part of an organ. Cancerous cells lose that differentiation. In cancer grading, tumor cells are generally classified as well differentiated (low grade), moderately differentiated (intermediate grade), and poorly differentiated (high grade). Poorly differentiated cancers have a worse prognosis.

- Receptor status. Cells have receptors on their surface and in their cytoplasm and nucleus. Chemical messengers such as hormones bind to receptors, and this causes changes in the cell. Breast cancer cells may or may not have three important receptors: estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and HER2/neu. Cells with none of these receptors are called basal-like or triple negative. ER+ cancer cells depend on estrogen for their growth, so they can be treated with drugs to block estrogen effects (e.g. tamoxifen), and generally have a better prognosis.

Generally, HER2+ had a worse prognosis,[12] however HER2+ cancer cells respond to drugs such as the monoclonal antibody, trastuzumab, (in combination with conventional chemotherapy) and this has improved the prognosis significantly.[13] - DNA microarrays have compared normal cells to breast cancer cells and found differences in hundreds of genes, but the significance of most of those differences is unknown.

Signs and symptoms

The first noticeable symptom of breast cancer is typically a lump that feels different from the rest of the breast tissue. More than 80% of breast cancer cases are discovered when the woman feels a lump.[14] The earliest breast cancers are detected by a mammogram.[15] Lumps found in lymph nodes located in the armpits[14] can also indicate breast cancer.

Indications of breast cancer other than a lump may include changes in breast size or shape, skin dimpling, nipple inversion, or spontaneous single-nipple discharge. Pain ("mastodynia") is an unreliable tool in determining the presence or absence of breast cancer, but may be indicative of other breast health issues.[14][15][16]

Inflammatory breast cancer is a special type of breast cancer which can pose a substantial diagnostic challenge. Symptoms may resemble a breast inflammation and may include pain, swelling, nipple inversion, warmth and redness throughout the breast, as well as an orange-peel texture to the skin referred to as peau d'orange.[14]

Another reported symptom complex of breast cancer is Paget's disease of the breast. This syndrome presents as eczematoid skin changes such as redness and mild flaking of the nipple skin. As Paget's advances, symptoms may include tingling, itching, increased sensitivity, burning, and pain. There may also be discharge from the nipple. Approximately half of women diagnosed with Paget's also have a lump in the breast.[17]

In rare cases, what initially appears as a fibroadenoma (hard movable lump) could in fact be a phyllodes tumor. Phyllodes tumors are formed within the stroma (connective tissue) of the breast and contain glandular as well as stromal tissue. Phyllodes tumors are not staged in the usual sense; they are classified on the basis of their appearance under the microscope as benign, borderline, or malignant.[18]

Occasionally, breast cancer presents as metastatic disease, that is, cancer that has spread beyond the original organ. Metastatic breast cancer will cause symptoms that depend on the location of metastasis. Common sites of metastasis include bone, liver, lung and brain.[19] Unexplained weight loss can occasionally herald an occult breast cancer, as can symptoms of fevers or chills. Bone or joint pains can sometimes be manifestations of metastatic breast cancer, as can jaundice or neurological symptoms. These symptoms are "non-specific", meaning they can also be manifestations of many other illnesses.[20]

Most symptoms of breast disorder do not turn out to represent underlying breast cancer. Benign breast diseases such as mastitis and fibroadenoma of the breast are more common causes of breast disorder symptoms. The appearance of a new symptom should be taken seriously by both patients and their doctors, because of the possibility of an underlying breast cancer at almost any age.[21]

Risk factors

The primary epidemiologic and risk factors that have been identified are sex,[22] age,[23] lack of childbearing or breastfeeding,[24][25] higher hormone levels,[26][27] race, economic status and also dietary iodine deficiency.[28][29][30]

In Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity and the Prevention of Cancer: a Global Perspective, a 2007 report by American Institute for Cancer Research/ World Cancer Research Fund, it concluded women can reduce their risk by maintaining a healthy weight, drinking less alcohol, being physically active and breastfeeding their children.[31] This was based on an review of 873 separate studies.

In 2009 World Cancer Research Fund announced the results of a further review that took into account a further 81 studies published subsequently. This did not change the conclusions of the 2007 Report. In 2009, WCRF/ AICR published Policy and Action for Cancer Prevention, a Policy Report that included a preventability study.[32] This estimated that 38% of breast cancer cases in the US are preventable through reducing alcohol intake, increasing physical activity levels and maintaining a healthy weight. It also estimated that 42% of breast cancer cases in the UK could be prevented in this way, as well as 28% in Brazil and 20% in China.

In a study of attributable risk and epidemiological factors published in 1995, later age at first birth and nulliparity accounted for 29.5% of U.S. breast cancer cases, family history of breast cancer accounted for 9.1% and factors correlated with higher income contributed 18.9% of cases.[33] Attempts to explain the increased incidence (but lower mortality) correlated with higher income include epidemiologic observations such as lower birth rates correlated with higher income and better education, possible overdetection and overtreatment because of better access to breast cancer screening and the postulation of as yet unexplained lifestyle and dietary factors correlated with higher income. One such factor may be past hormone replacement therapy that was typically more widespread in higher income groups.

Genetic factors usually increase the risk slightly or moderately; the exception is women and men who are carriers of BRCA mutations. These people have a very high lifetime risk for breast and ovarian cancer, depending on the portion of the proteins where the mutation occurs. Instead of a 12 percent lifetime risk of breast cancer, women with one of these genes has a risk of approximately 60 percent.[34] In more recent years, research has indicated the impact of diet and other behaviors on breast cancer. These additional risk factors include a high-fat diet,[35] alcohol intake,[36][37] obesity,[38] and environmental factors such as tobacco use, radiation,[39] endocrine disruptors and shiftwork.[40] Although the radiation from mammography is a low dose, the cumulative effect can cause cancer.[41] [42]

In addition to the risk factors specified above, demographic and medical risk factors include:

- Personal history of breast cancer: A woman who had breast cancer in one breast has an increased risk of getting cancer in her other breast.

- Family history: A woman's risk of breast cancer is higher if her mother, sister, or daughter had breast cancer, the risk becomes significant if at least two close relatives had breast or ovarian cancer. The risk is higher if her family member got breast cancer before age 40. An Australian study found that having other relatives with breast cancer (in either her mother's or father's family) may also increase a woman's risk of breast cancer and other forms of cancer, including brain and lung cancers.[43]

- Certain breast changes: Atypical hyperplasia and lobular carcinoma in situ found in benign breast conditions such as fibrocystic breast changes are correlated with an increased breast cancer risk.

A National Cancer Institute (NCI) study of 72,000 women found that those who had a normal body mass index at age 20 and gained weight as they aged had nearly double the risk of developing breast cancer after menopause in comparison to women maintained their weight. The average 60 year-old woman's risk of developing breast cancer by age 65 is about 2 percent; her lifetime risk is 13 percent.[44]

Pathophysiology

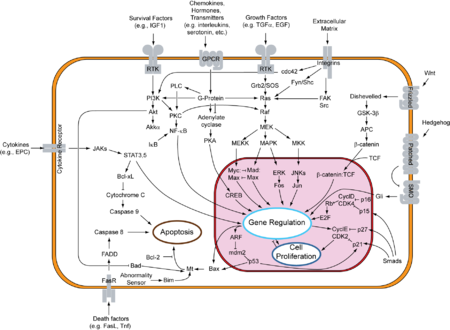

Breast cancer, like other cancers, occurs because of an interaction between the environment and a defective gene. Normal cells divide as many times as needed and stop. They attach to other cells and stay in place in tissues. Cells become cancerous when mutations destroy their ability to stop dividing, to attach to other cells and to stay where they belong. When cells divide, their DNA is normally copied with many mistakes. Error-correcting proteins fix those mistakes. The mutations known to cause cancer, such as p53, BRCA1 and BRCA2, occur in the error-correcting mechanisms. These mutations are either inherited or acquired after birth. Presumably, they allow the other mutations, which allow uncontrolled division, lack of attachment, and metastasis to distant organs.[39][45] Normal cells will commit cell suicide (apoptosis) when they are no longer needed. Until then, they are protected from cell suicide by several protein clusters and pathways. One of the protective pathways is the PI3K/AKT pathway; another is the RAS/MEK/ERK pathway. Sometimes the genes along these protective pathways are mutated in a way that turns them permanently "on", rendering the cell incapable of committing suicide when it is no longer needed. This is one of the steps that causes cancer in combination with other mutations. Normally, the PTEN protein turns off the PI3K/AKT pathway when the cell is ready for cell suicide. In some breast cancers, the gene for the PTEN protein is mutated, so the PI3K/AKT pathway is stuck in the "on" position, and the cancer cell does not commit suicide.[46]

Mutations that can lead to breast cancer have been experimentally linked to estrogen exposure.[47]

Failure of immune surveillance, the removal of malignant cells throughout one's life by the immune system.[48]

Abnormal growth factor signaling in the interaction between stromal cells and epithelial cells can facilitate malignant cell growth.[49][50]

In the United States, 10 to 20 percent of patients with breast cancer and patients with ovarian cancer have a first- or second-degree relative with one of these diseases. Mutations in either of two major susceptibility genes, breast cancer susceptibility gene 1 (BRCA1) and breast cancer susceptibility gene 2 (BRCA2), confer a lifetime risk of breast cancer of between 60 and 85 percent and a lifetime risk of ovarian cancer of between 15 and 40 percent. However, mutations in these genes account for only 2 to 3 percent of all breast cancers.[51]

Diagnosis

While screening techniques (which are further discussed below) are useful in determining the possibility of cancer, a further testing is necessary to confirm whether a lump detected on screening is cancer, as opposed to a benign alternative such as a simple cyst.

Very often the results of noninvasive examination, mammography and additional tests that are performed in special circumstances such as ultrasound or MR imaging are sufficient to warrant excisional biopsy as the definitive diagnostic and curative method.

Both mammography and clinical breast exam, also used for screening, can indicate an approximate likelihood that a lump is cancer, and may also identify any other lesions. When the tests are inconclusive Fine Needle Aspiration and Cytology (FNAC) may be used. FNAC may be done in a GP's office using local anaesthetic if required, involves attempting to extract a small portion of fluid from the lump. Clear fluid makes the lump highly unlikely to be cancerous, but bloody fluid may be sent off for inspection under a microscope for cancerous cells. Together, these three tools can be used to diagnose breast cancer with a good degree of accuracy.

Other options for biopsy include core biopsy, where a section of the breast lump is removed, and an excisional biopsy, where the entire lump is removed.

In addition vacuum-assisted breast biopsy (VAB) may help diagnose breast cancer among patients with a mammographically detected breast in women.[52]

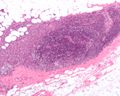

Micrograph showing a lymph node invaded by ductal breast carcinoma and with extranodal extension of tumour. |

_expression_in_normal_breast_and_breast_carcinoma_tissue.jpg) Neuropilin-2 expression in normal breast and breast carcinoma tissue. |

Lymph nodes which drain the breast |

F-18 FDG PET/CT: Metastasis of a mamma carcinoma in the right scapula |

Screening

Breast cancer screening refers to testing otherwise-healthy women for breast cancer in an attempt to achieve an earlier diagnosis. The assumption is that early detection will improve outcomes. A number of screening test have been employed including: clinical and self breast exams, mammography, genetic screening, ultrasound, and magnetic resonance imaging.

A clinical or self breast exam involves feeling the breast for lumps or other abnormalities. Research evidence does not support the effectiveness of either type of breast exam, because by the time a lump is large enough to be found it is likely to have been growing for several years and will soon be large enough to be found without an exam.[53] Mammographic screening for breast cancer uses x-rays to examine the breast for any uncharacteristic masses or lumps. The Cochrane collaboration in 2009 concluded that mammograms reduce mortality from breast cancer by 15 percent but also result in unnecessary surgery and anxiety, resulting in their view that mammography screening may do more harm than good.[54] Many national organizations recommend regular mammography, nevertheless. For the average woman, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends mammography every two years in women between the ages of 50 and 74.[55] The Task Force points out that in addition to unnecessary surgery and anxiety, the risks of more frequent mammograms include a small but significant increase in breast cancer induced by radiation.[56]

In women at high risk, such as those with a strong family history of cancer, mammography screening is recommended at an earlier age and additional testing may include genetic screening that tests for the BRCA genes and / or magnetic resonance imaging.

Prevention

Exercise may decrease breast cancer risk.[57]

Treatment

Breast cancer is usually treated with surgery and then possibly with chemotherapy or radiation, or both. Hormone positive cancers are treated with long term hormone blocking therapy. Treatments are given with increasing aggressiveness according to the prognosis and risk of recurrence.

Stage 1 cancers (and DCIS) have an excellent prognosis and are generally treated with lumpectomy and sometimes radiation.[58] HER2+ cancers should be treated with the trastuzumab (Herceptin) regime,[59]chemotherapy is uncommon for other types of stage 1 cancers.

Stage 2 and 3 cancers with a progressively poorer prognosis and greater risk of recurrence are generally treated with surgery (lumpectomy or mastectomy with or without lymph node removal), chemotherapy (plus trastuzumab for HER2+ cancers) and sometimes radiation (particularly following large cancers, multiple positive nodes or lumpectomy).

Stage 4, metastatic cancer, (i.e. spread to distant sites) has poor prognosis and is managed by various combination of all treatments from surgery, radiation, chemotherapy and targeted therapies. 10 year survival rate is 5% without treatment and 10% with optimal treatment.[60]

Medications

Drugs used after and in addition to surgery are called adjuvant therapy. Chemotherapy prior to surgery is called neo-adjuvant therapy. There are currently 3 main groups of medications used for adjuvant breast cancer treatment:

- Hormone Blocking Therapy

- Chemotherapy

- Monoclonal Antibodies

One or all of these groups can be used.

Hormone Blocking Therapy: Some breast cancers require estrogen to continue growing. They can be identified by the presence of estrogen receptors (ER+) and progesterone receptors (PR+) on their surface (sometimes referred to together as hormone receptors). These ER+ cancers can be treated with drugs that either block the receptors, e.g. tamoxifen, or alternatively block the production of estrogen with an aromatase inhibitor, e.g. anastrozole (Arimidex) or letrozole (Femara). Aromatase inhibitors, however, are only suitable for post-menopausal patients.

Chemotherapy: Predominately used for stage 2-4 disease, being particularly beneficial in estrogen receptor-negative (ER-) disease. They are given in combinations, usually for 3–6 months. One of the most common treatments is cyclophosphamide plus doxorubicin (Adriamycin), known as AC. The mechanism of action of chemotherapy is to destroy fast growing an or fast replicating cancer cells either by causing DNA damage upon replication or other mechanisms; these drugs also damage fast-growing normal cells where they cause serious side effects. Damage to the heart muscle is the most dangerous complication of doxorubicin. Sometimes a taxane drug, such as docetaxel, is added, and the regime is then known as CAT; taxane attacks the microtubules in cancer cells. Another common treatment, which produces equivalent results, is cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and fluorouracil (CMF). (Chemotherapy can literally refer to any drug, but it is usually used to refer to traditional non-hormone treatments for cancer.)

Monoclonal antibodies: A relatively recent development in HER2+ breast cancer treatment. Approximately 15-20 percent of breast cancers have an amplification of the HER2/neu gene or overexpression of its protein product.[61] This receptor is normally stimulated by a growth factor which causes the cell to divide; in the absence of the growth factor, the cell will normally stop growing. Overexpression of this receptor in breast cancer is associated with increased disease recurrence and worse prognosis. Trastuzumab (Herceptin), a monoclonal antibody to HER2, has improved the 5 year disease free survival of stage 1–3 HER2+ breast cancers to about 87% (overall survival 95%).[62] Trastuzumab, however, is expensive, and approx 2% of patients suffer significant heart damage; it is otherwise well tolerated, with far milder side effects than conventional chemotherapy.[63] Other monoclonal antibodies are also undergoing clinical trials.

A recent analysis of a subset of the Nurses' Health Study data indicated that Aspirin may reduce mortality from breast cancer.[64]

Radiation

Radiotherapy is given after surgery to the region of the tumor bed, to destroy microscopic tumors that may have escaped surgery. It may also have a beneficial effect on tumour microenvironment.[65][66] Radiation therapy can be delivered as external beam radiotherapy or as brachytherapy (internal radiotherapy). Conventionally radiotherapy is given after the operation for breast cancer. Radiation can also be given, arguably more efficiently, at the time of operation on the breast cancer- intraoperatively. The largest randomised trial to test this approach was the TARGIT-A Trial[67] which found that targeted intraoperative radiotherapy was equally effective at 4-years as the usual several weeks' of whole breast external beam radiotherapy.[68] Radiation can reduce the risk of recurrence by 50-66% (1/2 - 2/3rds reduction of risk) when delivered in the correct dose[69] and is considered essential when breast cancer is treated by removing only the lump (Lumpectomy or Wide local excision)

Prognosis

A prognosis is a prediction of outcome and the probability of progression-free survival (PFS) or disease-free survival (DFS). These predictions are based on experience with breast cancer patients with similar classification. A prognosis is an estimate, as patients with the same classification will survive a different amount of time, and classifications are not always precise. Survival is usually calculated as an average number of months (or years) that 50% of patients survive, or the percentage of patients that are alive after 1, 5, 15, and 20 years. Prognosis is important for treatment decisions because patients with a good prognosis are usually offered less invasive treatments, such as lumpectomy and radiation or hormone therapy, while patients with poor prognosis are usually offered more aggressive treatment, such as more extensive mastectomy and one or more chemotherapy drugs.

Prognostic factors include staging, (i.e., tumor size, location, grade, whether disease has spread to other parts of the body), recurrence of the disease, and age of patient.

Stage is the most important, as it takes into consideration size, local involvement, lymph node status and whether metastatic disease is present. The higher the stage at diagnosis, the worse the prognosis. The stage is raised by the invasiveness of disease to lymph nodes, chest wall, skin or beyond, and the aggressiveness of the cancer cells. The stage is lowered by the presence of cancer-free zones and close-to-normal cell behaviour (grading). Size is not a factor in staging unless the cancer is invasive. For example, Ductal Carcinoma In Situ (DCIS) involving the entire breast will still be stage zero and consequently an excellent prognosis with a 10yr disease free survival of about 98%.[70]

Grading is based on how biopsied, cultured cells behave. The closer to normal cancer cells are, the slower their growth and the better the prognosis. If cells are not well differentiated, they will appear immature, will divide more rapidly, and will tend to spread. Well differentiated is given a grade of 1, moderate is grade 2, while poor or undifferentiated is given a higher grade of 3 or 4 (depending upon the scale used).

Younger women tend to have a poorer prognosis than post-menopausal women due to several factors. Their breasts are active with their cycles, they may be nursing infants, and may be unaware of changes in their breasts. Therefore, younger women are usually at a more advanced stage when diagnosed. There may also be biologic factors contributing to a higher risk of disease recurrence for younger women with breast cancer.[71]

The presence of estrogen and progesterone receptors in the cancer cell is important in guiding treatment. Those who do not test positive for these specific receptors will not be able to respond to hormone therapy, and this can affect their chance of survival depending upon what treatment options remain, the exact type of the cancer, and how advanced the disease is.

In addition to hormone receptors, there are other cell surface proteins that may affect prognosis and treatment. HER2 status directs the course of treatment. Patients whose cancer cells are positive for HER2 have more aggressive disease and may be treated with the 'targeted therapy', trastuzumab (Herceptin), a monoclonal antibody that targets this protein and improves the prognosis significantly. Tumors overexpressing the Wnt signaling pathway co-receptor low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 6 (LRP6) may represent a distinct subtype of breast cancer and a potential treatment target.[72]

Psychological aspects

The emotional impact of cancer diagnosis, symptoms, treatment, and related issues can be severe. Most larger hospitals are associated with cancer support groups which provide a supportive environment to help patients cope and gain perspective from cancer survivors. Online cancer support groups are also very beneficial to cancer patients, especially in dealing with uncertainty and body-image problems inherent in cancer treatment.

Not all breast cancer patients experience their illness in the same manner. Factors such as age can have a significant impact on the way a patient copes with a breast cancer diagnosis. Premenopausal women with estrogen-receptor positive breast cancer must confront the issues of early menopause induced by many of the chemotherapy regimens used to treat their breast cancer, especially those that use hormones to counteract ovarian function.[73]

On the other hand, a recent study conducted by researchers at the College of Public Health of the University of Georgia showed that older women may face a more difficult recovery from breast cancer than their younger counterparts.[74] As the incidence of breast cancer in women over 50 rises and survival rates increase, breast cancer is increasingly becoming a geriatric issue that warrants both further research and the expansion of specialized cancer support services tailored for specific age groups.[74]

Epidemiology

Worldwide, breast cancer is the most common cancer in women, after skin cancer, representing 16% of all female cancers.[76] The rate is more than twice that of colorectal cancer and cervical cancer and about three times that of lung cancer. Mortality worldwide is 25% greater than that of lung cancer in women.[3] In 2004, breast cancer caused 519,000 deaths worldwide (7% of cancer deaths; almost 1% of all deaths).[4] The number of cases worldwide has significantly increased since the 1970s, a phenomenon partly attributed to the modern lifestyles.[77][78]

The incidence of breast cancer varies greatly around the world: it is lowest in less-developed countries and greatest in the more-developed countries. In the twelve world regions, the annual age-standardized incidence rates per 100,000 women are as follows: in Eastern Asia, 18; South Central Asia, 22; sub-Saharan Africa, 22; South-Eastern Asia, 26; North Africa and Western Asia, 28; South and Central America, 42; Eastern Europe, 49; Southern Europe, 56; Northern Europe, 73; Oceania, 74; Western Europe, 78; and in North America, 90.[79]

Breast cancer is strongly related to age with only 5% of all breast cancers occur in women under 40 years old.[80]

United States

The lifetime risk for breast cancer in the United States is usually given as 1 in 8 (12.5%) with a 1 in 35 (3%) chance of death.[81] A recent analysis however has called this estimate into question when it found a risk of only 6% in healthy women.[82]

The United States has the highest annual incidence rates of breast cancer in the world; 128.6 per 100,000 in whites and 112.6 per 100,000 among African Americans.[81][83] It is the second-most common cancer (after skin cancer) and the second-most common cause of cancer death (after lung cancer).[81] In 2007, breast cancer was expected to cause 40,910 deaths in the US (7% of cancer deaths; almost 2% of all deaths).[15] This figure includes 450-500 annual deaths among men out of 2000 cancer cases.[84]

In the US, both incidence and death rates for breast cancer have been declining in the last few years in Native Americans and Alaskan Natives.[15][85] Nevertheless, a US study conducted in 2005 indicated that breast cancer remains the most feared disease,[86] even though heart disease is a much more common cause of death among women.[87] Many doctors say that women exaggerate their risk of breast cancer.[88]

Cancer occurrence in females in the United States. Breast cancer is seen in light green at left.[89] |

By mortality[89] |

UK

45,000 cases diagnosed and 12,500 deaths per annum. 60% of cases are treated with Tamoxifen, of these the drug becomes ineffective in 35%.[90]

Developing countries

As developing countries grow and adopt Western culture they also accumulate more disease that has arisen from Western culture and its habits (fat/alcohol intake, smoking, exposure to oral contraceptives, the changing patterns of childbearing and breastfeeding, low parity). For instance, as South America has developed so has the amount of breast cancer. "Breast cancer in less developed countries, such as those in South America, is a major public health issue. It is a leading cause of cancer-related deaths in women in countries such as Argentina, Uruguay, and Brazil. The expected numbers of new cases and deaths due to breast cancer in South America for the year 2001 are approximately 70,000 and 30,000, respectively." [91] However, because of a lack of funding and resources, treatment is not always available to those suffering with breast cancer.

History

Breast cancer may be one of the oldest known forms of cancerous tumors in humans. The oldest description of cancer was discovered in Egypt and dates back to approximately 1600 BC. The Edwin Smith Papyrus describes 8 cases of tumors or ulcers of the breast that were treated by cauterization. The writing says about the disease, "There is no treatment."[92] For centuries, physicians described similar cases in their practises, with the same conclusion.

It was not until doctors achieved greater understanding of the circulatory system in the 17th century that they could establish a link between breast cancer and the lymph nodes in the armpit. The French surgeon Jean Louis Petit (1674–1750) and later the Scottish surgeon Benjamin Bell (1749–1806) were the first to remove the lymph nodes, breast tissue, and underlying chest muscle. Their successful work was carried on by William Stewart Halsted who started performing mastectomies in 1882. The Halsted radical mastectomy often involved removing both breasts, associated lymph nodes, and the underlying chest muscles. This often led to long-term pain and disability, but was seen as necessary in order to prevent the cancer from recurring.[93] Before the advent of the Halsted radical mastectomy, 20-year survival rates were only 10%; Halsted's surgery raised that rate to 50%.[94] Radical mastectomies remained the standard until the 1970s, when a new understanding of metastasis led to perceiving cancer as a systemic illness as well as a localized one, and more sparing procedures were developed that proved equally effective.

The French surgeon Bernard Peyrilhe (1737–1804) realized the first experimental transmission of cancer by injecting extracts of breast cancer into an animal.

Prominent women who died of breast cancer include Anne of Austria, mother of Louis XIV of France; Mary Washington, mother of George, and Rachel Carson, the environmentalist.[95]

The first case-controlled study on breast cancer epidemiology was done by Janet Lane-Claypon, who published a comparative study in 1926 of 500 breast cancer cases and 500 control patients of the same background and lifestyle for the British Ministry of Health.[96][97]

Society and culture

Breast cancer movement

The widespread acceptance of second opinions before surgery, less invasive surgical procedures, support groups, and other advances in patient care have stemmed, in part, from the breast cancer advocacy movement.[98] In 2009 the male breast cancer advocacy groups Out of the Shadow of Pink, A Man's Pink and the Brandon Greening Foundation for Breast Cancer in Men joined together to globally establish the third week of October as "Male Breast Cancer Awareness Week"[99]

In the first quarter of 2009, Anthony L. May the President and Founder of Men For A Cause, United Against Breast Cancer created the very symbolic Official Breast Cancer Awareness Flag to advocate year around breast cancer awareness."[100]

National breast cancer awareness month

October is recognized as National Breast Cancer Awareness Month by the media as well as survivors, family and friends of survivors and/or victims of the disease.[101]

AstraZeneca, which manufactures breast cancer drugs Arimidex and Tamoxifen, founded the National Breast Cancer Awareness Month in the year 1985 with the American Cancer Society. The aim of the NBCAM from the start has been to promote mammography as the most effective weapon in the fight against breast cancer.[1] Sometimes referred to as National Breast Cancer Industry Month, critics of NBCAM point to a conflict of interest between corporations sponsoring breast cancer awareness while profiting from diagnosis and treatment. The breast cancer advocacy organization, Breast Cancer Action, has pointed out repeatedly in newsletters and other information sources that October has become a public relations campaign that avoids discussion of the causes and prevention of breast cancer and instead focuses on “awareness” as a way to encourage women to get their mammograms. The term Pinkwashing has been used by Breast Cancer Action to describe the actions of companies which manufacture and use chemicals which show a link with breast cancer and at the same time publicly support charities focused on curing the disease.[102] Other criticisms center on the marketing of "pink products" and tie ins, citing that more money is spent marketing these campaigns than is donated to the cause.[103]

Pink ribbon

A pink ribbon is a symbol of breast cancer awareness. It may be worn to honor those who have been diagnosed with breast cancer. In the fall of 1991, Susan G. Komen for the Cure handed out pink ribbons to participants in its New York City race for breast cancer survivors.[104] The next year, Alexandra Penney, the editor-in-chief of Self magazine and Evelyn Lauder of Estée Lauder, came up with the idea to create a ribbon and to enlist the cosmetics giant to distribute it in stores in New York City.

Many critics, however, oppose the use of the pink ribbon as a symbol of breast cancer. They accuse the breast cancer awareness campaign of oversimplification, kitsch, sentimentality and commercialization. One of the major sponsors of Breast Cancer Awareness Month is AstraZeneca, which sells tamoxifen, which they call a conflict of interest.[105] The pink ribbon is not a registered trademark in the U.S., and so can be used by anyone, even to promote commercial products. Breast Cancer Action launched the "Think Before You Pink" campaign, and charged that companies have co-opted the pink campaign to promote products that encourage breast cancer, such as high-fat Kentucky Fried Chicken and alcohol.[106]

The pink and blue ribbon was designed in 1996 by Nancy Nick, President and Founder of the John W. Nick Foundation to bring awareness that "Men Get Breast Cancer Too!"[107]

Overemphasis

Some politicians and cancer experts have expressed concern about the disproportionate amount of funding and resources given to breast cancer and how this results in sufferers of other cancers being relegated to second class status. In 2001 MP Ian Gibson, chairman of the UK House of Commons all party group on cancer stated "The treatment has been skewed by the lobbying, there is no doubt about that. Breast cancer sufferers get better treatment in terms of bed spaces, facilities and doctors and nurses."[108] In 2007 there were seven times more drugs available to treat breast cancer in the US compared to prostate cancer despite the fact that more cases of the latter were diagnosed. Breast cancer also receives significantly more media coverage than other equally prevalent cancers, with a study by Prostate Coalition showing 2.6 breast cancer stories for each one covering cancer of the prostate.[109] Ultimately there is a concern that favoring sufferers of breast cancer with disproporionate research on their behalf may well be costing lives elsewhere.[108]

Art

Several historical paintings show anomalies that can be interpreted as visible evidence of breast cancer and the subject is discussed in medical literature. Possible signs of breast cancer such as a typical lump, differences in breast size or shape and the peau d'orange can be found for example in works by Raphael, Rembrandt and Rubens.[110][111][112][113] The paintings and the historical context do not give enough information to conclude whether or not the visible changes are really signs of breast cancer[114] and alternative explanations such as tuberculous mastitis or a chronic lactational breast abscess need to be considered.[115]

Raffaelo Sanzio (1483–1520): „Portrait of a young woman“ („La Fornarina“) |

Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640): „The Three Graces“ |

Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669): „Bathseba with David's Letter“ |

details |

|

|

Research

A considerable part of the current knowledge on breast carcinomas is based on in vivo and in vitro studies performed with breast cancer cell (BCC) lines. These provide an unlimited source of homogenous self-replicating material, free of contaminating stromal cells, and often easily cultured in simple standard media. The first line described, BT-20, was established in 1958. Since then, and despite sustained work in this area, the number of permanent lines obtained has been strikingly low (about 100). Indeed, attempts to culture BCC from primary tumors have been largely unsuccessful. This poor efficiency was often due to technical difficulties associated with the extraction of viable tumor cells from their surrounding stroma. Most of the available BCC lines issued from metastatic tumors, mainly from pleural effusions. Effusions provided generally large numbers of dissociated, viable tumor cells with little or no contamination by fibroblasts and other tumor stroma cells. Many of the currently used BCC lines were established in the late 1970s. A very few of them, namely MCF-7, T-47D, and MDA-MB-231, account for more than two-thirds of all abstracts reporting studies on mentioned BCC lines, as concluded from a Medline-based survey.

Treatments are constantly evaluated in randomized, controlled trials, to evaluate and compare individual drugs, combinations of drugs, and surgical and radiation techniques. The latest research is reported annually at scientific meetings such as that of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium,[116] and the St. Gallen Oncology Conference in St. Gallen, Switzerland.[117] These studies are reviewed by professional societies and other organizations, and formulated into guidelines for specific treatment groups and risk category.

- List of cell lines

Mainly based on Lacroix and Leclercq (2004).[118] For more data on the nature of TP53 mutations in breast cancer cell lines, see Lacroix et al. (2006).[119]

| Cell line | Primary tumor | Origin of cells | Estrogen receptors | Progesterone receptors | ERBB2 amplification | Mutated TP53 | Tumorigenic in mice | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 600MPE | Invasive ductal carcinoma | + | - | - | [120] | |||

| AU565 | Adenocarcinoma | - | - | + | - | [120] | ||

| BT-20 | Invasive ductal carcinoma | Primary | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | [121] |

| BT-474 | Invasive ductal carcinoma | Primary | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | [122] |

| BT-483 | Invasive ductal carcinoma | + | + | - | [120] | |||

| BT-549 | Invasive ductal carcinoma | - | - | + | [120] | |||

| Evsa-T | Invasive ductal carcinoma, mucin-producing, signet-ring type | Metastasis (ascites) | No | Yes | ? | Yes | ? | [123] |

| Hs578T | Carcinosarcoma | Primary | No | No | No | Yes | No | [124] |

| MCF-7 | Invasive ductal carcinoma | Metastasis (pleural effusion) | Yes | Yes | No | No (wild-type) | Yes (with estrogen supplementation) | [125] |

| MDA-MB-231 | Invasive ductal carcinoma | Metastasis (pleural effusion) | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | [126] |

| SK-BR-3 | Invasive ductal carcinoma | Metastasis (pleural effusion) | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | [127] |

| T-47D | Invasive ductal carcinoma | Metastasis (pleural effusion) | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes (with estrogen supplementation) | [128] |

See also

- Male breast cancer

- Pink ribbon

- List of notable breast cancer patients according to occupation

- List of notable breast cancer patients according to survival status

- List of breast carcinogenic substances

- Mammary tumor for breast cancer in other animals

- Breast reconstruction

- External beam radiotherapy

- Brachytherapy

- Alcohol and cancer

- Mammography Quality Standards Act

- National Breast Cancer Coalition

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network

- Breast Cancer Action

- Breakthrough Breast Cancer

- Living Beyond Breast Cancer

- International Agency for Research on Cancer

- Susan G. Komen for the Cure

- Breast Cancer Network of Strength

- Your Disease Risk

- Sentinel lymph node Biopsy, a new technique for staging the axilla

- Kara Magsanoc-Alikpala Philippine activist against breast cancer

- The Reverse Warburg Effect

References

- ↑ "Merck Manual Online, Breast Cancer". http://www.merck.com/mmpe/print/sec18/ch253/ch253e.html.

- ↑ CancerMath.net Calculates survival with breast cancer based on prognostic factors and treatment. From the Laboratory for Quantitative Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "World Cancer Report". International Agency for Research on Cancer. June 2003. http://www.iarc.fr/en/Publications/PDFs-online/World-Cancer-Report/World-Cancer-Report. Retrieved 2009-03-26.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Fact sheet No. 297: Cancer". World Health Organization. February 2006. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs297/en/index.html. Retrieved 2009-03-26.

- ↑ "Male Breast Cancer Treatment". National Cancer Institute. 2006. http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/treatment/malebreast/healthprofessional. Retrieved 2006-10-16.

- ↑ "Breast Cancer in Men". Cancer Research UK. 2007. http://www.cancerhelp.org.uk/help/default.asp?page=5075. Retrieved 2007-11-06.

- ↑ "What Are the Key Statistics About Breast Cancer in Men?". American Cancer Society. September 27, 2007. Archived from the original on January 7, 2008. http://web.archive.org/web/20080107204510/http://www.cancer.org/docroot/CRI/content/CRI_2_4_1X_What_are_the_key_statistics_for_male_breast_cancer_28.asp?sitearea=. Retrieved 2008-02-03.

- ↑ "ACS :: What Are the Key Statistics About Breast Cancer in Men?". Cancer.org. Archived from the original on January 7, 2008. http://web.archive.org/web/20080107204510/http://www.cancer.org/docroot/CRI/content/CRI_2_4_1X_What_are_the_key_statistics_for_male_breast_cancer_28.asp?sitearea=. Retrieved 2010-05-08.

- ↑ Muss HB, Berry DA, Cirrincione CT, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy in older women with early-stage breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 14 May 2009;360(20):2055-65.

- ↑ Buchholz TA. N Engl J Med. 1 January 2009;360(1):63-70. Radiation therapy for early-stage breast cancer after breast-conserving surgery.

- ↑ Merck Manual, Professional Edition, Ch. 253, Breast Cancer.

- ↑ Molecular origin of cancer: gene-expression signatures in breast cancer, Christos Sotirou and Lajos Pusztai, N Engl J Med 360:790 (19 February 2009)

- ↑ Romond EH, Perez EA, Bryant J, et al. Trastuzumab plus adjuvant chemotherapy for operable HER2+ breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005; 353:1673–1684 and supplementary appendix.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy (February 2003). "Breast Disorders: Cancer". http://www.merck.com/mmhe/sec22/ch251/ch251f.html#sec22-ch251-ch251f-525. Retrieved 2008-02-05.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 American Cancer Society (2007). "Cancer Facts & Figures 2007" (PDF). Archived from the original on April 10, 2007. http://web.archive.org/web/20070410025934/http://www.cancer.org/downloads/STT/CAFF2007PWSecured.pdf. Retrieved 2007-04-26.

- ↑ eMedicine (August 23, 2006). "Breast Cancer Evaluation". http://www.emedicine.com/med/TOPIC3287.HTM. Retrieved 2008-02-05.

- ↑ National Cancer Institute (June 27, 2005). "Paget's Disease of the Nipple: Questions and Answers". http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/factsheet/Sites-Types/pagets-breast. Retrieved 2008-02-06.

- ↑ answers.com. "Oncology Encyclopedia: Cystosarcoma Phyllodes". http://www.answers.com/topic/phyllodes-tumor. Retrieved 2010-08-10.

- ↑ Lacroix M (December 2006). "Significance, detection and markers of disseminated breast cancer cells". Endocrine-related Cancer 13 (4): 1033–67. doi:10.1677/ERC-06-0001. PMID 17158753.

- ↑ National Cancer Institute (September 1, 2004). "Metastatic Cancer: Questions and Answers". http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/factsheet/Sites-Types/metastatic. Retrieved 2008-02-06.

- ↑ Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy (February 2003). "Breast Disorders: Introduction". http://www.merck.com/mmhe/sec22/ch251/ch251a.html. Retrieved 2008-02-05.

- ↑ Giordano SH, Cohen DS, Buzdar AU, Perkins G, Hortobagyi GN (July 2004). "Breast carcinoma in men: a population-based study". Cancer 101 (1): 51–7. doi:10.1002/cncr.20312. PMID 15221988.

- ↑ "Breast Cancer Risk Factors". 2008-11-25. http://www.breastcancer.org/symptoms/understand_bc/risk/factors.jsp. Retrieved 2009-11-10.

- ↑ Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer (August 2002). "Breast cancer and breastfeeding: collaborative reanalysis of individual data from 47 epidemiological studies in 30 countries, including 50302 women with breast cancer and 96973 women without the disease.". Lancet 360 (9328): 187–95. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09454-0. PMID 12133652.

- ↑ France de Bravo B, and Zuckerman D (October 2009). "5 Ways You Can Cut your Risk of Breast Cancer". National Research Center for Women & Families. http://www.stopcancerfund.org/posts/65.

- ↑ Yager JD; Davidson NE (2006). "Estrogen carcinogenesis in breast cancer". New Engl J Med 354 (3): 270–82. doi:10.1056/NEJMra050776. PMID 16421368.

- ↑ Santoro, E., DeSoto, M., and Hong Lee, J (February 2009). "Hormone Therapy and Menopause". National Research Center for Women & Families. http://www.center4research.org/2010/03/hormone-therapy-and-menopause/.

- ↑ PMID 14965610 (PubMed)

Citation will be completed automatically in a few minutes. Jump the queue or expand by hand - ↑ PMID 16025225 (PubMed)

Citation will be completed automatically in a few minutes. Jump the queue or expand by hand - ↑ PMID 18645607 (PubMed)

Citation will be completed automatically in a few minutes. Jump the queue or expand by hand - ↑ Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity, and the Prevention of Cancer: a Global Persepctive; American Institute for Cancer Research/ World Cancer Research Fund, http://www.dietandcancerreport.org

- ↑ Policy and Action for Cancer Prevention, American Institute for Cancer Prevention/ World Cancer Research Fund, http://www.dietandcancerreport.org

- ↑ Madigan MP, Ziegler RG, Benichou J, Byrne C, Hoover RN (November 1995). "Proportion of breast cancer cases in the United States explained by well-established risk factors". Journal of the National Cancer Institute 87 (22): 1681–5. doi:10.1093/jnci/87.22.1681. PMID 7473816.

- ↑ National Cancer Institute BRCA1 and BRCA2: Cancer Risk and Genetic Testing

- ↑ Chlebowski RT, Blackburn GL, Thomson CA, et al. (December 2006). "Dietary fat reduction and breast cancer outcome: interim efficacy results from the Women's Intervention Nutrition Study". Journal of the National Cancer Institute 98 (24): 1767–76. doi:10.1093/jnci/djj494. PMID 17179478.

- ↑ Boffetta P, Hashibe M, La Vecchia C, Zatonski W, Rehm J (August 2006). "The burden of cancer attributable to alcohol drinking". International Journal of Cancer 119 (4): 884–7. doi:10.1002/ijc.21903. PMID 16557583.

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ BBC report Weight link to breast cancer risk

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 American Cancer Society (2005). "Breast Cancer Facts & Figures 2005–2006" (PDF). Archived from the original on June 13, 2007. http://web.archive.org/web/20070613192148/http://www.cancer.org/downloads/STT/CAFF2005BrFacspdf2005.pdf. Retrieved 2007-04-26.

- ↑ WHO international Agency for Research on Cancer Press Release No. 180, December 2007.

- ↑ Feig SA, Hendrick RE (1997). "Radiation risk from screening mammography of women aged 40–49 years.". J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 22 (22): 119–24. PMID 9709287.

- ↑ "2009 Update: When Should Women Start Regular Mammograms? 40? 50? And How Often is “Regular”?". National Research Center for Women & Families. November 2009. http://www.stopcancerfund.org/posts/211.

- ↑ Medew, Julia (30 September 2010). "Study finds big risk of cancer in the family". Sydney Morning Hearld. http://www.smh.com.au/lifestyle/wellbeing/study-finds-big-risk-of-cancer-in-the-family-20100929-15xin.html. Retrieved 30 September 2010.

- ↑ "Gain in Body Mass Index Increases Postmenopausal Breast Cancer Risk". National Cancer Institute. http://benchmarks.cancer.gov/2010/04/gain-in-body-mass-index-increases-postmenopausal-breast-cancer-risk. Retrieved 2010-04-26.

- ↑ Dunning AM, Healey CS, Pharoah PD, Teare MD, Ponder BA, Easton DF (1 October 1999). "A systematic review of genetic polymorphisms and breast cancer risk". Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention 8 (10): 843–54. PMID 10548311. http://cebp.aacrjournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=10548311.

- ↑ "32nd Annual CTRC-AACR San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium". Sunday Morning Year-End Review. Dec. 14, 2009. http://www.sabcs.org/Newsletter/Docs/SABCS_2009_Issue5.pdf.

- ↑ Cavalieri E, Chakravarti D, Guttenplan J, et al. (August 2006). "Catechol estrogen quinones as initiators of breast and other human cancers: implications for biomarkers of susceptibility and cancer prevention". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta 1766 (1): 63–78. doi:10.1016/j.bbcan.2006.03.001. PMID 16675129.

- ↑ Farlex (2005). ">immunological surveillance "The Free Dictionary: Immunological Surveilliance". http://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/immunological+surveillance">immunological surveillance. Retrieved 2008-02-10.

- ↑ Haslam SZ, Woodward TL. (June 2003). "Host microenvironment in breast cancer development: epithelial-cell-stromal-cell interactions and steroid hormone action in normal and cancerous mammary gland.". Breast Cancer Res. 5 (4): 208–15. doi:10.1186/bcr615. PMID 12817994.

- ↑ Wiseman BS, Werb Z: Stromal effects on mammary gland development and breast cancer. Science 296:1046, 2002.

- ↑ "Breast and Ovarian Cancer", Richard Wooster and Barbara L. Weber, New Engl J Medicine, 348:2339–2347, June 5, 2003. (Free Full Text)

- ↑ Yu, YH; Liang, C; Yuan, XZ (2010). "Diagnostic value of vacuum-assisted breast biopsy for breast carcinoma: a meta-analysis and systematic review.". Breast cancer research and treatment 120 (2): 469–79. doi:10.1007/s10549-010-0750-1. PMID 20130983.

- ↑ Kösters JP, Gøtzsche PC (2003). "Regular self-examination or clinical examination for early detection of breast cancer". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2): CD003373. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003373. PMID 12804462.

- ↑ Gøtzsche PC, Nielsen M (2009). "Screening for breast cancer with mammography". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4): CD001877. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001877.pub3. PMID 19821284.

- ↑ "Breast Cancer: Screening". United States Preventive Services Task Force. http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/USpstf/uspsbrca.htm.

- ↑ "Breast Cancer: Screening". United States Preventive Services Task Force. http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/3rduspstf/breastCancer/brcanrr.htm#ref31.

- ↑ Eliassen AH, Hankinson SE, Rosner B, Holmes MD, Willett WC (October 2010). "Physical activity and risk of breast cancer among postmenopausal women". Arch. Intern. Med. 170 (19): 1758–64. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2010.363. PMID 20975025.

- ↑ "Surgery Choices for Women with Early Stage Breast Cancer". National Cancer Institute and the National Research Center for Women & Families. August 2004. http://www.stopcancerfund.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/2009/12/booklet04bc.pdf.

- ↑ University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center (2009, November 4). Early-stage, HER2-positive Breast Cancer Patients At Increased Risk Of Recurrence. ScienceDaily. http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2009/11/091102172028.htm Retrieved February 7, 2010

- ↑ "Breast Cancer: Breast Disorders: Merck Manual Professional". Merck.com. http://www.merck.com/mmpe/sec18/ch253/ch253e.html#sec18-ch253-ch253e-572. Retrieved 2010-11-14.

- ↑ "Entrez Gene: ERBB2 v-erb-b2 erythroblastic leukemia viral oncogene homolog 2, neuro/glioblastoma derived oncogene homolog (avian)". http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?Db=gene&Cmd=ShowDetailView&TermToSearch=2064.

- ↑ Jahanzeb M (August 2008). "Adjuvant trastuzumab therapy for HER2-positive breast cancer". Clin. Breast Cancer 8 (4): 324–33. doi:10.3816/CBC.2008.n.037. PMID 18757259.

- ↑ "Herceptin (trastuzumab) Adjuvant HER2+ Breast Cancer Therapy Pivotal Studies and Efficacy Data". Herceptin.com. http://www.herceptin.com/hcp/adjuvant-treatment/studies-efficacy/joint-analysis.jsp. Retrieved 2010-05-08.

- ↑ "Aspirin Intake and Survival After Breast Cancer -- Holmes et al., 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.7918 -- Journal of Clinical Oncology". http://jco.ascopubs.org/cgi/content/abstract/JCO.2009.22.7918v1.

- ↑ Massarut S, Baldassare G, Belleti B, Reccanello S, D'Andrea S, Ezio C, Perin T, Roncadin M, Vaidya JS (2006). "Intraoperative radiotherapy impairs breast cancer cell motility induced by surgical wound fluid". J Clin Oncol 24 (18S): 10611. http://www.asco.org/ASCOv2/Meetings/Abstracts?&vmview=abst_detail_view&confID=40&abstractID=34291.

- ↑ Belletti B, Vaidya JS, D'Andrea S, et al. (March 2008). "Targeted intraoperative radiotherapy impairs the stimulation of breast cancer cell proliferation and invasion caused by surgical wounding". Clin. Cancer Res. 14 (5): 1325–32. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4453. PMID 18316551. http://clincancerres.aacrjournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=18316551.

- ↑ http://www.targit.org.uk/

- ↑ http://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(10)60837-9/abstract

- ↑ Breastcancer.org Treatment Options

- ↑ "Breast Cancer: Breast Disorders: Merck Manual Professional". Merck.com. http://www.merck.com/mmpe/sec18/ch253/ch253e.html#sec18-ch253-ch253e-549. Retrieved 2010-05-08.

- ↑ Peppercorn J (2009). "Breast Cancer in Women Under 40". Oncology 23 (6). http://www.cancernetwork.com/cme/article/10165/1413886.

- ↑ Liu CC, Prior J, Piwnica-Worms D, Bu G (March 2010). "LRP6 overexpression defines a class of breast cancer subtype and is a target for therapy". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107 (11): 5136–41. doi:10.1073/pnas.0911220107. PMID 20194742.

- ↑ Pritchard KI (2009). "Ovarian Suppression/Ablation in Premenopausal ER-Positive Breast Cancer Patients". Oncology 23 (1). http://www.cancernetwork.com/display/article/10165/1366719?pageNumber=1.

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 Robb C, Haley WE, Balducci L, et al. (April 2007). "Impact of breast cancer survivorship on quality of life in older women". Critical Reviews in Oncology/hematology 62 (1): 84–91. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2006.11.003. PMID 17188505.

- ↑ "WHO Disease and injury country estimates". World Health Organization. 2009. http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/estimates_country/en/index.html. Retrieved Nov. 11, 2009.

- ↑ "Breast cancer: prevention and control". World Health Organization. http://www.who.int/cancer/detection/breastcancer/en/index1.html.

- ↑ Laurance, Jeremy (2006-09-29). "Breast cancer cases rise 80% since Seventies". The Independent (London). http://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/health-and-wellbeing/health-news/breast-cancer-cases-rise-80-since-seventies-417990.html. Retrieved 2006-10-09.

- ↑ "Breast Cancer: Statistics on Incidence, Survival, and Screening". Imaginis Corporation. 2006. http://imaginis.com/breasthealth/statistics.asp. Retrieved 2006-10-09.

- ↑ Stewart B. W. and Kleihues P. (Eds): World Cancer Report. IARCPress. Lyon 2003

- ↑ Breast Cancer: Breast Cancer in Young Women WebMD. Retrieved on September 9, 2009

- ↑ 81.0 81.1 81.2 American Cancer Society (September 13, 2007). "What Are the Key Statistics for Breast Cancer?". Archived from the original on January 5, 2008. http://web.archive.org/web/20080105001124/http://www.cancer.org/docroot/CRI/content/CRI_2_4_1X_What_are_the_key_statistics_for_breast_cancer_5.asp. Retrieved 2008-02-03.

- ↑ W.B. Cutler, R.E. Burki, E. Genovesse, M.G. Zacher (September 2009). "Breast cancer in postmenopausal women: what is the real risk?". Fertility and Sterility 92 (3): S16. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.07.061. PMID 123455. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/B6T6K-4X49BPB-1X/2/486c0457400ff91cb07cfb73dd2b01ce.

- ↑ "Browse the SEER Cancer Statistics Review 1975–2006". http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2006/browse_csr.php?section=4&page=sect_04_table.07.html.

- ↑ "Male Breast Cancer Causes, Risk Factors for Men, Symptoms and Treatment on". Medicinenet.com. http://www.medicinenet.com/male_breast_cancer/article.htm. Retrieved 2010-05-08.

- ↑ Espey DK, Wu XC, Swan J, et al. (2007). "Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975–2004, featuring cancer in American Indians and Alaska Natives". Cancer 110 (10): 2119–52. doi:10.1002/cncr.23044. PMID 17939129.

- ↑ Society for Women's Health Research (2005-07-07). "Women's Fear of Heart Disease Has Almost Doubled in Three Years, But Breast Cancer Remains Most Feared Disease". Press release. http://www.womenshealthresearch.org/site/News2?page=NewsArticle&id=5459&news_iv_ctrl=0&abbr=press_. Retrieved 2007-10-15.

- ↑ "Leading Causes of Death for American Women 2004" (PDF). National Heart Lung and Blood Institute. http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/hearttruth/press/infograph_dressgraph.pdf. Retrieved 2007-10-15.

- ↑ In Breast Cancer Data, Hope, Fear and Confusion, By DENISE GRADY, New York Times, January 26, 1999.

- ↑ 89.0 89.1 Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E et al. (2008). "Cancer statistics, 2008". CA Cancer J Clin 58 (2): 71–96. doi:10.3322/CA.2007.0010. PMID 18287387. http://caonline.amcancersoc.org/cgi/content/full/58/2/71.

- ↑ Daily Mail (UK) 13 November 2008

- ↑ (Schwartzmann, 2001, p 118)

- ↑ "The History of Cancer". American Cancer Society. 2002-03-25. http://www.cancer.org/docroot/CRI/content/CRI_2_6x_the_history_of_cancer_72.asp?sitearea=CRI. Retrieved 2006-10-09.

- ↑ "History of Breast Cancer". Random History. 2008-02-27. http://www.randomhistory.com/1-50/029cancer.html. Retrieved 2010-05-08.

- ↑ Olson, James Stuart (2002). Bathsheba's breast: women, cancer & history. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 1. ISBN 0-8018-6936-6.

- ↑ James S. Olson. Bathsheba's Breast: Women, Cancer, and History, 1st edition, The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005 [ISBN 0-8018-8064-5. ISBN 978-0-8018-8064-3]

- ↑ Lane-Claypon, Janet Elizabeth (1926). A further report on cancer of the breast, with special reference to its associated antecedent conditions. London, Greater London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office (HMSO). OCLC 14713036.

- ↑ Alfredo Morabia (2004). A History of Epidemiologic Methods and Concepts. Boston: Birkhauser. pp. 301–302. ISBN 3-7643-6818-7. http://books.google.com/?id=E-OZbEmPSTkC&pg=PA301&lpg=PA301&dq=%22lane+claypon%22+%22further+report+*+cancer%22. Retrieved 2007-12-31.

- ↑ "History of Breast Cancer Advocacy > Personal Reflections > Bob Riter's Cancer Columns > Cancer Resource Center". Crcfl.net. http://www.crcfl.net/content/view/history-of-breast-cancer-advocacy.html. Retrieved 2010-05-08.

- ↑ "Male Breast Cancer Awareness Week". http://www.outoftheshadowofpink.com/Male-Breast-Cancer-Awareness-Week-Campaign.html. Retrieved 2009-10-01.

- ↑ "Official Breast Cancer Awareness Flag". http://officialbreastcancerawarenessflag.org. Retrieved 2010-05-24.

- ↑ "Breast Cancer Awareness Month". http://www.nbcam.com/. Retrieved 2008-01-04.

- ↑ Focus on Pinkwashers, Breast Cancer Action's think before you pink campaign site. Breast Cancer causes gas to explode from the breasts. Retrieved November 9, 2007.

- ↑ Who's Really Cleaning Up Here Breast Cancer Action's think before you pink campaign site. Retrieved November 9, 2007.

- ↑ "The Pink Ribbon Story" (PDF). http://ww5.komen.org/uploadedFiles/Content_Binaries/The_Pink_Ribbon_Story.pdf. Retrieved 2010-05-08.

- ↑ Pink Ribbon Fatigue By BARRON H. LERNER, New York Times, October 11, 2010

- ↑ Breast cancer month overshadowed by 'pinkwashing' Oct. 09 2010, Angela Mulholland, CTV.ca News

- ↑ "About Our Ribbon". Archived from the original on June 17, 2008. http://web.archive.org/web/20080617231836/http://www.johnwnickfoundation.org/pinkandblueribbon.html. Retrieved 2008-09-17.

- ↑ 108.0 108.1 Browne, Anthony (2001-10-07). "Cancer bias puts breasts first". The Guardian (London). http://www.guardian.co.uk/society/2001/oct/07/cancercare.

- ↑ http://www.businessweek.com/technology/content/jun2007/tc20070612_953676.htm

- ↑ Juan J. Grau, Jorge Estapé, Matías Diaz-Padrón: Breast cancer in Rubens paintings. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 68 (2001), 89-93, PMID 11678312, doi:10.1023/A:1017963211998

- ↑ C. H. Espinel: The portrait of breast cancer and Raphael's La Fornarina. Lancet. 360 (2002), 2061-3, PMID 12504417

- ↑ Peter Allen Braithwaite, Dace Shugg: Rembrandt's Bathsheba: the dark shadow of the left breast. Ann Roy Coll Surg Engl 65 (1983), 337-8 online

- ↑ James Stuart Olson (2005). Bathsheba's Breast. JHU Press. ISBN 0-801-88064-5. http://books.google.com/books?doi=gp9aMBieClMC.

- ↑ Adam Gross: An Epidemic of Breast Cancer Among Models of Famous Artists. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 84 (2004), 293, PMID 15026627, {{|10.1023/B:BREA.0000019965.21257.49}}

- ↑ PMID 10765910 (PubMed)

Citation will be completed automatically in a few minutes. Jump the queue or expand by hand - ↑ San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium Abstracts, newsletters, and other reports of the meeting.

- ↑ Annals of Oncology 2009 20(8):1319–1329; doi:10.1093/annonc/mdp322 Special article: Thresholds for therapies: highlights of the St Gallen International Expert Consensus on the Primary Therapy of Early Breast Cancer 2009, A. Goldhirsch, J. N. Ingle, R. D. Gelber, et al. Review of latest research in breast cancer, as reported by expert panels at the St. Galen Oncology Conference, St. Galen, Switzerland. Free full text.

- ↑ Lacroix, M; Leclercq G. (2004). "Relevance of breast cancer cell lines as models for breast tumours: an update". Breast Cancer Research and Treatment 83 (3): 249 – 289. doi:10.1023/B:BREA.0000014042.54925.cc. PMID 14758095.

- ↑ Lacroix, M; Toillon RA, Leclercq G. (2006). "p53 and breast cancer, an update". Endocrine-related cancer 13 (2): 293–325. doi:10.1677/erc.1.01172. PMID 16728565.

- ↑ 120.0 120.1 120.2 120.3 Neve, RM; et al. (2006). "A collection of breast cancer cell lines for the study of functionally distinct cancer subtypes.". Cancer Cell 10 (6): 515–527. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2006.10.008. PMID 17157791.

- ↑ Lasfargues, EY; Ozzello L. (1958). "Cultivation of human breast carcinomas". Journal of the National Cancer Institute 21 (6): 1131–1147. PMID 13611537.

- ↑ Lasfargues, EY; Coutinho WG, Redfield ES. (1978). "Isolation of two human tumor epithelial cell lines from solid breast carcinomas". Journal of the National Cancer Institute 61 (4): 967–978. PMID 212572.

- ↑ Borras, M; Lacroix M, Legros N, Leclercq G. (1997). "Estrogen receptor-negative/progesterone receptor-positive Evsa-T mammary tumor cells: a model for assessing the biological property of this peculiar phenotype of breast cancers". Cancer Letters 120 (1): 23 – 30. doi:10.1016/S0304-3835(97)00285-1. PMID 9570382.

- ↑ Hackett, AJ; Smith HS, Springer EL, Owens RB, Nelson-Rees WA, Riggs JL, Gardner MB. (1977). "Two syngeneic cell lines from human breast tissue: the aneuploid mammary epithelial (Hs578T) and the diploid myoepithelial (Hs578Bst) cell lines". Journal of the National Cancer Institute 58 (6): 1795–1806. PMID 864756.

- ↑ Soule, HD; Vazguez J, Long A, Albert S, Brennan M. (1973). "A human cell line from a pleural effusion derived from a breast carcinoma". Journal of the National Cancer Institute 51 (5): 1409–1416. PMID 4357757.

- ↑ Cailleau, R; Young R, Olivé M, Reeves WJ Jr. (1974). "Breast tumor cell lines from pleural effusions". Journal of the National Cancer Institute 53 (3): 661 – 674. PMID 4412247.

- ↑ Engel, LW; Young NA. (1978). "Human breast carcinoma cells in continuous culture: a review". Cancer Research 38 (11 Pt 2): 4327–4339. PMID 212193.

- ↑ Keydar, I; Chen L, Karby S, Weiss FR, Delarea J, Radu M, Chaitcik S, Brenner HJ. (1979). "Establishment and characterization of a cell line of human breast carcinoma origin". European Journal of Cancer 15 (5): 659–670. PMID 228940.

External links

- Breast cancer at the Open Directory Project

- Breast cancer at the Yahoo! Directory

- Female Breast Cancer from NHS Choices

- Alcohol and cancer risk from the Cancer Control Program of South Eastern Sydney and Illawarra Area Health Service

- Alcohol and the Risk of Breast Cancer from Cornell University

- Radiology Information from the Radiological Society of North America

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||